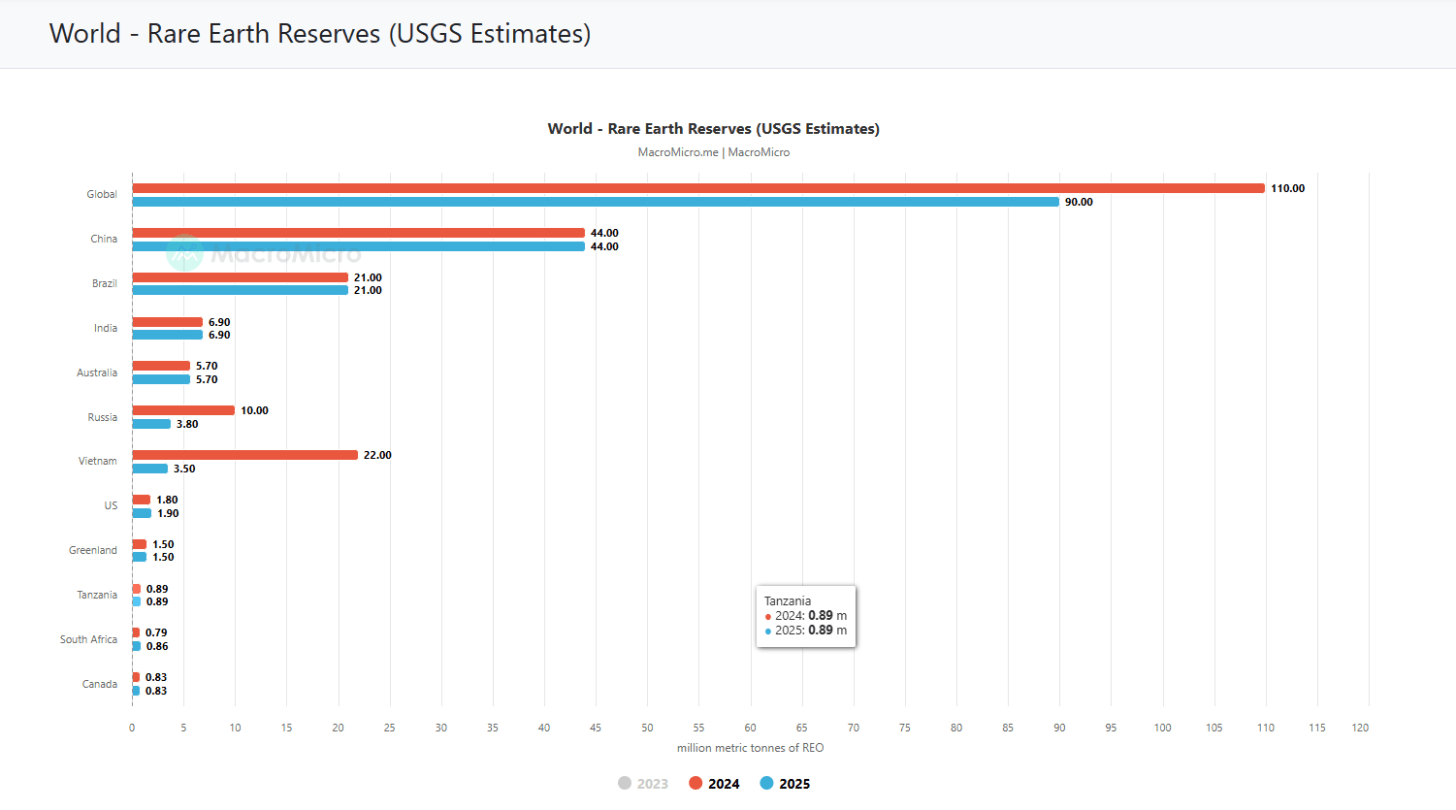

When I was younger, we used to refer to ‘rare’ as something seldom found. This has apparently changed when it comes to “rare earths” which are, in fact, not rare at all. USGS Rare Earths Summary 2025 puts it best “rare earths are relatively abundant in the Earth’s crust but rarely occur in concentrated and economically exploitable forms.”

You know me; I love an economically exploitable resource.

These 17 metallic elements are essential, inconvenient and messy to produce. They are also the backbone of modern life: from consumer tech (headphones, smartphones, VR gear) to industrial kit (EV drivetrains, offshore wind, robotics) and even defence hardware that relies on high-performance magnets or luminescent coatings. If it lights up, spins, or hums, it probably needs rare earths.

And, while rare earths are plentiful, very few countries actually want to produce them. Extracting and refining rare earths remains a complex and environmentally intensive process. For every tonne of rare earth material, you oust roughly 100 tonnes of other ore, leaving behind a toxic mess that’s expensive (and unpopular) to clean up.

Rare earths suffer from the same PR issue as nuclear energy. We need them for a low-carbon world, but the production process doesn’t fit neatly into the “clean and green” narrative. Square peg, round hole.

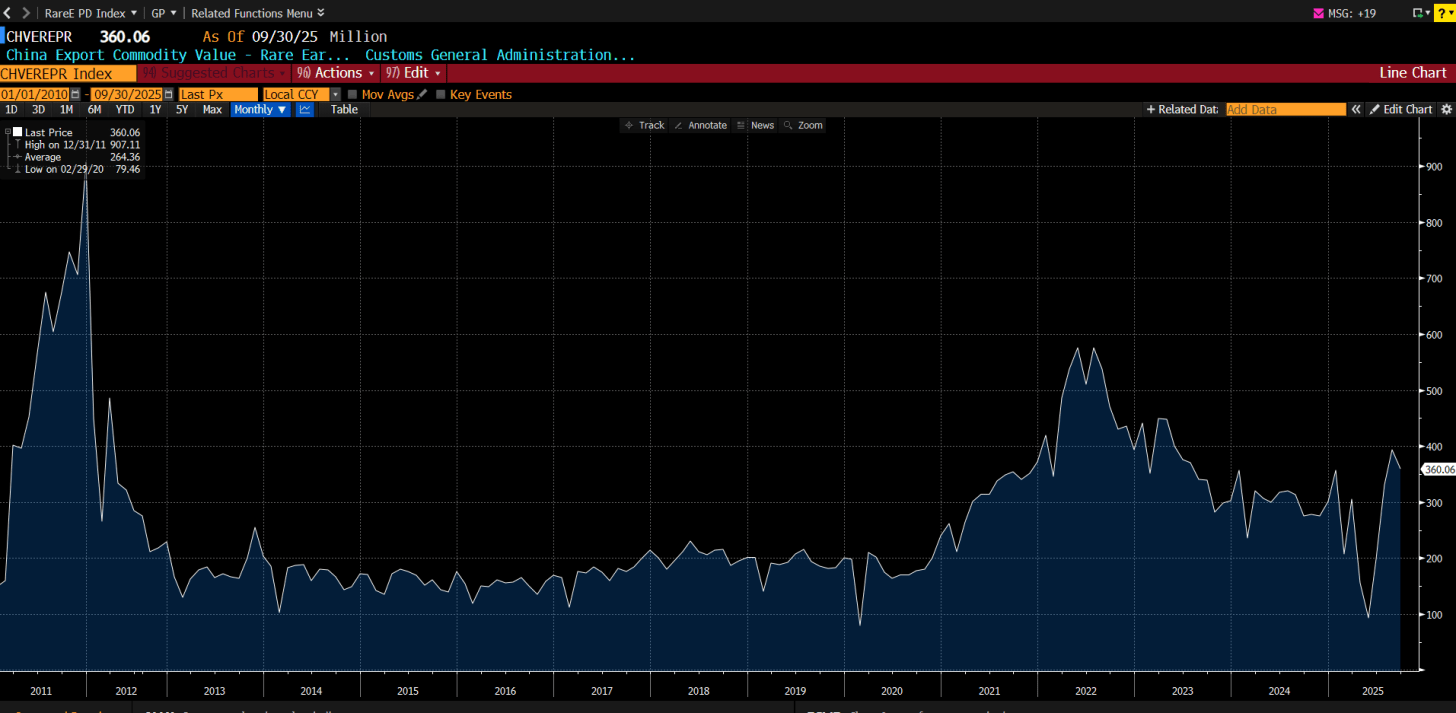

That’s why countries like China have dominated production for decades. They are willing to tolerate the environmental cost. The rest of the world isn’t.

It’s hard to believe that just a few decades ago, the U.S. was producing nearly all the world’s rare earths. But as environmental scrutiny tightened and regulations ramped up, production was largely shut down by the early 2000’s.

China stepped in to fill the void, and global dependence soon followed, cementing a strategic edge in the increasingly critical AI arms race.

Now, it seems, the West has recognised this and is scrambling to rebuild secure and transparent supply chains for these essential materials.

Australia holds significant rare earth reserves, estimated at 5.7 million metric tonnes in 2024, representing about 5.2% of the global total. The issue has never been geology; it’s been willingness to process.

Maybe what the sector really needs is a new story. Add two simple letters, “AI”, and watch the urgency grow. Australia recently inked an $8.5 billion deal with the U.S. to boost supply chain security and ramp up rare earth production. With East-West tensions always precarious and the energy transition inevitable, it seems now people are potentially more willing to get their hands dirty (whatever it takes to get that nuclear sub, Australia).

From the desk of IGB

Source post: Blackbull Research - Substack